This story appears in ESPN The Magazine’s Sept. 18 NFL Preview Issue. Subscribe today!

I‘m sitting here outside the hospital in my car taking deep breaths. I was told I need to take off of work to be trained on how to administer the [tracheostomy tube] and keep it clean and I actually think I’m in a state of shock:

How do I do this and work full time?

How do I do this and take care of a 20 year old special needs son?

How do I do this and run around with a 9 year old who dreams of modeling, acting, being a pageant princess and still maintain her GPA and make sure that she is a well balanced 9 year old?

How do I maintain the house and cook and clean?

When do I work out?

And my thoughts go to the NFL and I am numb, they knew but because of money hid it?

Who does this to people, to families?

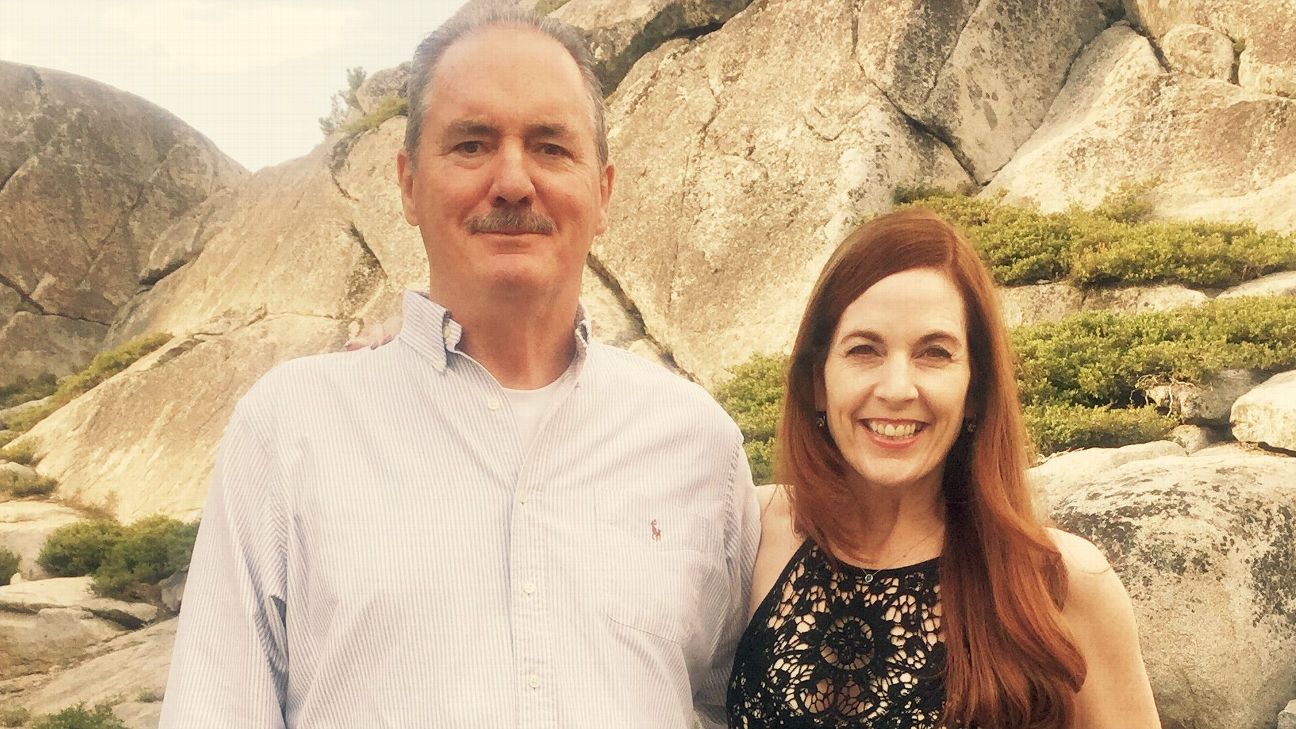

Rickey Dixon fights for his life and his family, as he awaits his NFL concussion settlement award.Benedict Evans for ESPN

IT’S A HOT summer evening in Dallas, and Lorraine Dixon is trying desperately not to fall apart. She’s holed up in her car outside of Williams P. Clements Jr. University Hospital, terrified. Tubes have been surgically inserted into her husband’s throat and stomach, procedures designed to help him eat and breathe. But in reality, they represent more work for Lorraine and heightened fears that the end is near. The doctors said her husband had three to five years to live. This is Year 4.

Lorraine’s mind is racing, but she can’t speak her thoughts, can’t give them life, so instead she texts them to a reporter who has been pressing for details of a life shaped by football in ways she never could have imagined.

Two days earlier, Boston University researchers had announced that, out of 111 brains of former NFL players they had studied, all but one was laden with a neurodegenerative disease. Behind those numbers are women like Lorraine Dixon — and perhaps thousands of others — battling the human dimensions of a growing crisis that reverberates outward, from the crippled men down through their entire families.

Some researchers — particularly those affiliated with the NFL and other sports leagues — have suggested that the connection between football and long-term brain damage is overstated: that the link between the two is unsettled, that the BU research is limited and skewed, and that the scope of the problem is likely far smaller than imagined. But there is a Facebook group called “Women of the NFL” that suggests otherwise. It has more than 2,000 members — wives, girlfriends, ex-wives, daughters, widows of former players — whose interaction these days often revolves around brain-addled men.

This, then, is not another story about the warriors who sacrificed their minds and bodies to build football into a $14 billion industry. Rather, this is the tale of the women behind the men; women who have now been thrust into the roles of caretakers, managing the lives of men who once embodied strength and self-reliance.

Men like Rickey Dixon, who played six seasons in the NFL, from 1988 to 1993, and was diagnosed four years ago, at age 47, with Lou Gehrig’s disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS). Today, Dixon is restricted largely to his bed and a wheelchair — unable to do anything independently. Other than think.

“He’s trapped in a body that doesn’t work,” says Lorraine, who has been married to Dixon for 24 years.

Or men like Gerry Sullivan, who played eight seasons in the NFL, from 1974 to 1981, and then two more in the USFL.

“So, he’s basically got, I always like to say, [10] years of pro football under his belt and, unfortunately, under his brain,” says Liz Nicholson Sullivan, who has been with Gerry for more than two decades; the two were married two years ago.

In 2004, at age 52, Gerry Sullivan was diagnosed with frontal lobe dementia. He’s now largely a shut-in, confined to their high-rise apartment in Chicago, fearful of going outside, paranoid and so forgetful that their home is riddled with Post-it notes.

For Lorraine Dixon, Liz Nicholson Sullivan and so many other women, their NFL experiences have been redefined in later years, colored by the transformations of these men and, now, by the legal battles they’re waging. It has fallen on them to navigate the NFL concussion case — the $1 billion settlement that stemmed from thousands of players suing the league over claims it hid the dangers of concussions. The settlement was supposed to provide much-needed money to ease their burdens; instead, for many, it has become a legal morass defined by battles with lawyers, predatory lenders and a complicated award process.

Says Nicholson Sullivan: “It is a very difficult world that we are living in right now in light of the lawsuit and in light of the enormous amount of, I won’t call them vultures, I will call them people that are coming out to profit from NFL families that are struggling with a loved one who is very sick.”

Says Lorraine Dixon, herself an attorney: “It’s just a bunch of greed going on, and it’s sickening.”

“Pound for pound, Rickey was probably one of the hardest-hitting guys that I ever played with, period. Bar none,” says Joe Kelly, who was a teammate of Dixon’s for three seasons. Courtesy Dixon Family

MORE THAN A dozen crosses adorn the walls outside Rickey Dixon’s bedroom. Some are wooden, others metal, some ornate, others plain. Inside, under the music and oration of religious programs that play regularly on the TV, are the sounds of a man fighting for his life. It’s a few weeks before Rickey will have the two tubes inserted into his body, and a breathing device whooshes methodically, up and down, up and down, providing critical aid to lungs that no longer can do their job.

In a hospital-type bed lies a man unrecognizable from the one who once used his body as a battering ram — spindly, gaunt, even emaciated. Dixon’s skin is like wrapping paper — there’s just enough to conceal the silhouette of a skeleton. His hands shake and his fists clench as he employs his knuckles to ploddingly punch out messages via text. Saliva sometimes drips from the sides of his mouth, requiring Lorraine or one of their children to wipe it off. Occasionally, he is lifted out of bed and placed in an electric wheelchair, but mostly he spends his days in bed, helpless.

“He can’t go to the bathroom by himself,” Lorraine says. “He can’t go bathe himself, can’t use a toothbrush by himself anymore, can’t feed himself.”

Dixon is 5-foot-11, and his playing weight was 177 pounds, hardly large for an NFL player. But he was a sculpted defensive back who patrolled the secondary, seeking and destroying any receiver or running back who dared enter his territory. Dixon had been a star coming out of the University of Oklahoma in 1987, where he’d led the Sooners to two national championship games (one win); in 1987, he won the Jim Thorpe Award, given to the nation’s top defensive back. He was the fifth pick in the 1988 draft and wound up playing five seasons with the Cincinnati Bengals and one with the Los Angeles Raiders.

“Pound for pound, Rickey was probably one of the hardest-hitting guys that I ever played with, period. Bar none,” says Joe Kelly, who was a teammate of Dixon’s for three seasons.

Retirement had seemed to be working for Rickey. He was out of football at 28 but went on to own a landscaping business, coach high school football and conduct motivational speeches for kids. And then, as it cruelly can, life pivoted. In spring 2013, Rickey fell while working out on a treadmill and began exhibiting some worrying signs.

“He eventually said he couldn’t feel the count of money, like the feel of money in your hand when you’re counting it,” says his 22-year-old son, RJ.

Two months later, doctors diagnosed Rickey with ALS and told him he probably had three to five years to live. The neurological disorder attacks the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord, stifling voluntary muscle movements as basic as walking, talking and chewing. The body withers away, while the mind remains intact. There is no cure. Before he got sick, Dixon weighed about 195 pounds. Today, he’s down to less than 120.

There’s debate about football’s role in players getting ALS. A 2012 study, published in the journal Neurology, suggests that former NFL players are four times more likely to die from the disease than the general population. More recently, research using rat models revealed that repeated blows led to an earlier onset of ALS symptoms, although another study examined head-injury history of ALS patients and determined that trauma was not associated with quicker development of the disease.

The Dixons say they believe football is the cause of Rickey’s ALS.

Asked to comment on Lorraine Dixon’s suggestion that the NFL covered up the dangers related to head trauma for the sake of money, a league spokesman provided a list of programs offered to current and former players: “These peer-to-peer programs help the players and their families transition into their post-NFL life and provide assistance for their mental, emotional, physical, financial well-being.”

Nevertheless, Lorraine, who does take advantage of at least one of these NFL programs, now battles to stay above water. Where she once dreamed of a retirement full of umbrella drinks, her life is now a numbing march from one responsibility to the next, with assistance from her oldest daughter, 27-year-old Brittanney, who at one point quit her job to help out at home; RJ, who transferred from the University of Tulsa to the University of North Texas, just an hour away; and nursing aides.

A typical day for Lorraine: Up at 6 a.m., wake her 21-year-old son, Cameron, who is intellectually disabled and himself requires full-time care. Get Cameron dressed and brush his teeth. Then wake 9-year-old Alana, a precocious pageant princess. Get everybody fed and then walk Cameron out to his school bus a little after 7. Come back to the house, wake Rickey, clean his face, empty his urinal, change him if necessary, brush his teeth and feed him. Return to Alana, brush her hair, make sure she has her stuff together and drive her to school. Catch the bus to work at the Environmental Protection Agency offices in downtown Dallas, about 20 miles from their home in suburban Red Oak. (“If I catch the bus, it’s great because I don’t have to pay parking and gas. And I’m able to sleep on the bus,” she says.) Her health insurance helps pay for nursing care for Rickey during the day and for Cameron when he gets home from school. So, Lorraine works her eight hours, then returns home to cook dinner, do the dishes, sweat over piles of laundry, work with Alana on her homework, help Cameron take a shower or a bath, set out his clothes for the next day, get him into bed, check in on Rickey, and get him bathed and ready for bed.

Then, finally, at about 10 p.m. — 16 hours after her day began — she’s done. She’ll spend some time with Rickey, then flee to the living room to watch Animal Planet or Nat Geo WILD. “Then I’ll lay down and go to sleep, and I’ll wake up and do it again.”

That’s a basic day. But with Cameron, the days and nights can become even more complicated. When he was 6, Cameron nearly died after developing encephalitis, a viral infection that causes inflammation of the brain. Ultimately, it left him unable to speak and his brain frozen in time. Now 21, he needs constant supervision and has regular seizures. Sometimes, Lorraine will have Brittanney sleep in Cameron’s room. “You have to watch Cameron because if he’s seizing and he’s getting up, he can hit his head, make him unconscious, bust his lip, bust his teeth,” Lorraine says. Cameron is like a toddler in a man’s body — forever trying to cause mischief, oblivious to implications. One night, Lorraine awoke to the sound of running water and discovered that Cameron had turned on the faucet in the kitchen sink and flooded it. “The next morning,” Lorraine says, laughing as she tells the story, “we have standing water from my bedroom, [the living room], the kitchen, the den and some of the hallway.” The bathroom doors are now childproofed, locked at all times, as are all ways in and out of the house.

And if that weren’t enough, Lorraine now finds herself immersed in the NFL concussion settlement, which stems from a lawsuit brought by thousands of former players who claimed the league hid the dangers of concussions. The first cases against the NFL were filed in August 2011, with an agreement reached and approved by the court in July 2014, a year after Rickey was diagnosed with ALS. The settlement created a grid that would pay players a certain amount based on the severity of their condition, the age at which they became sick and the number of years they played in the league. ALS was assigned one of the highest awards, putting the Dixons in line to collect $4.5 million.

But three years later, with the case delayed by objections and appeals, money is only now beginning to flow — and, with it, story after story of conflict and confusion. The Dixons are fighting with Zimmerman Reed, a law firm they initially hired in 2012 but fired in late 2015, after the preliminary settlement had been reached. Zimmerman Reed responded by filing a lien against the Dixons, arguing that the firm had earned 20 percent of their award — or about $900,000.

But that’s just one of more than 500 liens that have been filed in a case that has seen lawyers poaching clients from other attorneys by undercutting their fees. The protracted case has also spawned a cottage industry of predatory lending, with players taking out high-interest loans to provide quick cash. In 2014, Rickey Dixon took out a $50,000 loan in an effort to pay for experimental stem cell therapy in Southern California. Three-and-a-half years later, interest had ballooned the debt to $165,000.

Rickey was diagnosed two decades after his last NFL season. Within three years, Lorraine’s life had become chaos.

“It’s like three short years, zero to 100,” she says. “Like zero being, ‘We’re going to make this together, there’s nothing that comes up against us that we can’t tackle’ to 100 like, ‘Man, I have to do this — Lorraine, you have to do this — you can’t get sick, you can’t get tired, you have to push through, you have to push through.’ So, for me, it can be so draining.”

Wives of former NFL players care for their husbands battling debilitating brain diseases as they’re immersed in the NFL concussion settlement. Liz Nicholson Sullivan, wife of Gerry Sullivan, shares her story.Courtesy Liz Nicholson

LIZ NICHOLSON SULLIVAN is Gerry’s second wife and not a football fan. She never saw him play. When Liz’s sister-in-law introduced the two in 1996, Liz couldn’t have told you that Gerry once played every position on the offensive line in a single game, let alone that he was a member of the fabled Kardiac Kids, the 1980 Browns team that captivated Cleveland through a series of last-minute victories and a rare playoff run.

But if Nicholson Sullivan wasn’t an NFL wife then, she is one now. It has been more than a decade since Gerry was diagnosed with dementia, and although his dry sense of humor remains and he can recount with specificity many of his days in the NFL, his short-term memory is shot.

“Well, it’s difficult to say this, but I run his life,” Nicholson Sullivan says, as Gerry sits within earshot. “… He’s incapable of doing anything that he used to be able to do very easily.”

Liz and Gerry grew up in or around Chicago and have lived there much of their lives. Recently, they moved into a condo on the North Side; it’s a new neighborhood, but familiar enough. One day, Liz asked Gerry to go down the block to the dry cleaner. They had walked that block together several times before, and Liz says she repeatedly had shown him the business, prepping him for the moment he would run this errand.

“He called me six times in an hour to confirm where the dry cleaner was,” Liz says.

… It’s something the public doesn’t always like to hear about because they like to sit on a Sunday and watch their football games. But I’m here to tell you that the result is a lot of very sick men.

– Liz Nicholson Sullivan

Along with a handful of other spouses, Nicholson Sullivan has become something of a den mother in the NFL wives community, an increasingly vocal, organized and informed cadre of women thrust into juggling a mishmash of roles — from caretaker to legal proxy to patient advocate.

Although Nicholson Sullivan maintains a full-time job as a political consultant, this world has consumed her. She is on the board of directors of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, an advocacy organization focused on “the study, treatment and prevention of the effects of brain trauma in athletes.” The NFL veterans’ group Gridiron Greats recently honored her with its Sylvia Mackey Woman of the Year Award, whose namesake has been a champion around the issue of brain injury from football.

“It is every day for me,” Nicholson Sullivan says. “Every day is either caring for Gerry, managing Gerry’s life or communicating with my NFL sisters, if you will, because we’re all cut from the cloth, dealing with the same thing. … It’s almost like we could write a playbook about what happens with these guys that eventually have a neurodegenerative disease.”

A little more than a year ago, a private Facebook group called “Current and Former Wives of NFL Players” popped up. Tara Nesbit, whose husband, Jamar, played 11 years in the league before retiring after the 2009 season, says she was feeling increasingly disconnected from many of the women with whom she held a unique bond.

“It started strictly for unimportant reasons,” says Nesbit, who says her husband is having no cognitive issues. “Just to get women together.” Now, though, she says, “It has taken on a life of its own.”

Nesbit subsequently renamed the page “Women of the NFL,” and since a New York Times story about the group ran Aug. 7, Nesbit says she has added about 150 members — with still more lined up to be verified — bringing the total to 2,350. It has become the primary resource for women connected to men who played (or are playing) in the NFL. And these days, the majority of the conversation revolves around brain damage, the billion-dollar concussion settlement and the brain banks that are competing for donations.

“The page has been a godsend,” Nicholson Sullivan says.

And even as checks are now being cut from the settlement, many wives, former players and family members say they are scrambling to better understand how to get paid and to fend off a stream of unscrupulous opportunists.

“I’m navigating getting hit up every which way but Sunday by a guy who is telling me, ‘Oh, sign up the wives for an informational seminar,’ when in reality, it’s a lawyer that is trying to get these guys to sign on the dotted line to, you know, represent them, when they may already have a lawyer,” Nicholson Sullivan says. “Or [the] husbands who are impaired getting phone calls on their cellphone where a wife catches a husband and says, ‘Who are you talking to?’ And it’s someone that’s trying to sell them something, or sell them that they could file their claim for them or register them. Little do they know that this guy wants 35 percent of the award — if this man gets an award.”

All of which is fodder on the “Women of the NFL” Facebook page.

“We don’t have anyone else to tell this to, and we understand one another because we’re living it with our husbands,” Nicholson Sullivan says. “And it’s something the public doesn’t always like to hear about because they like to sit on a Sunday and watch their football games. But I’m here to tell you that the result is a lot of very sick men.”

In 1988, Dixon was a first-round draft pick; today, “he’s trapped in a body that doesn’t work,” says his wife, Lorraine. Focus on Sport/Getty Images

AROUND THE TIME last month that Rickey Dixon first went to the hospital to have breathing and feeding tubes inserted, Lorraine says she received a check from the settlement administrator for a little more than $1.5 million — far less than the $4.5 million she expected. There was the $900,000 held back until the dispute with Zimmerman Reed is settled, and an additional $270,000 withheld for assorted legal and administrative fees. Still, that left about $1.8 million missing. Lorraine says she was told this remainder was to cover medical liens to repay her private insurance, but she says there’s no way the bill could be this high.

It’s all she can do not to get crushed under the weight of this life. But if Lorraine is crushed, who parents her four kids? Who manages Cameron’s life? Who helps 9-year-old Alana chase her dreams, gets her up in the morning, makes her breakfast, sends her off to school, helps with her homework? Who totes Alana from one pageant to the next, buys and helps select the outfits, brushes her hair, does her makeup?

Who makes the money necessary to live? Sure, Rickey made a good living during his six years in the NFL, but he retired 24 years ago. That money is long gone. The Dixons are not in dire straits financially, but Lorraine needs to keep her job as a lawyer with the EPA to maintain the critical health insurance it provides for Rickey’s and Cameron’s care.

And, of course, who takes care of Rickey — whose body is disappearing before Lorraine’s eyes? And now there are these two tubes, one protruding from a hole cut into his throat to help her husband breathe, the other a feeding tube inserted through a notch in his stomach. Both have to be cleaned and maintained to keep Rickey alive.

Each morning, the gauze around the breathing tube, soiled with mucus, must be removed, the area cleaned and new gauze put in place. Three times a day, Rickey requires breathing treatment, which includes sticking a separate tube down his throat to suction out any phlegm.

The doctors have told Lorraine that she needs to fully grasp these processes before Rickey can leave the hospital.

And so as she sits alone in her car, in the hospital parking lot, the text continues to pour out of her, the words providing catharsis in a world that seems unmanageable.

I look at Rickey laying in the hospital bed, trac in his throat, tube in his stomach, has lost 57% of his body weight, can’t talk and can barely move and I think about the NFL and I ask Jesus to help me forgive them.

… the NFL truly they couldn’t know, no one could be that cruel and then I remember

We fight the NFL to help our loved ones that they made millions of dollars off of

We fight our own lawyers so that they don’t overcharge us for minimal work and fees already paid for by the NFL

We fight to keep money from the lead attorney’s to administer a plan that they want the victims of the suit to pay for

We fight the Claim and Lien Administrators for placing a hold on monies without justification and I realize….

Money is truly the Root of all Evil.

Baumgart is a feature producer for ESPN.